Welcome to Part II of Honouring Tea in our University of Alberta Library’s month-long focus on China and Chinese culture. In a world of chaos, nothing comforts me more than the traditional process of brewing Chinese tea. It’s a methodical and thoughtful routine that is as warm and soothing to my soul as it is to my body. This quiet and meditative ritual helps me connect me to my Chinese culture, and as I mentioned in my ode to dim sum in our May 2021 Asian Heritage Month blog series, these connections are limited.

While Part I of Honouring Tea gave an abridged overview of Chinese tea and a few of my go-to library holdings, Part II identifies specific teas and the teaware used to get the most out of the delicate brews. I will also repeat my disclaimer from Part I, in that I am not an expert in Chinese tea; I am an aficionado. There are subtleties and histories beyond the limitations of this blog and I hope that this series will inspire you to learn more.

Chinese tea is prized for its taste, scent, and healthful properties. Like many items on the market, there can be varying scales of quality which can impact the overall experience of consumption. Focus in restaurants can be more on the food, with tea as an after-thought. The tea is an assortment of coarsely chopped, likely machine-harvested leaves and stems. If this is someone’s only exposure to Chinese tea, I can understand the hesitancy to feel jazzed about consuming it for pleasure.

Lu Yü’s The Classic of Tea, is the original definitive essay on Chinese tea, referenced by most books and articles in our Bloomsbury Food Library database. The essay is broken into three chapters: the first refers to the beginnings and manufacture of tea; the second refers to the tools used; and the third refers to the process of brewing the tea.

Throughout the essay Lu Yü’s steps reflect care and thoughtfulness in order to achieve a tea’s best result. With a wide variety of tea and processing methods, attention to detail is a must: sourcing high quality leaves, consideration as to where water is sourced from, water temperature, and the use of the proper tools to complete the task.

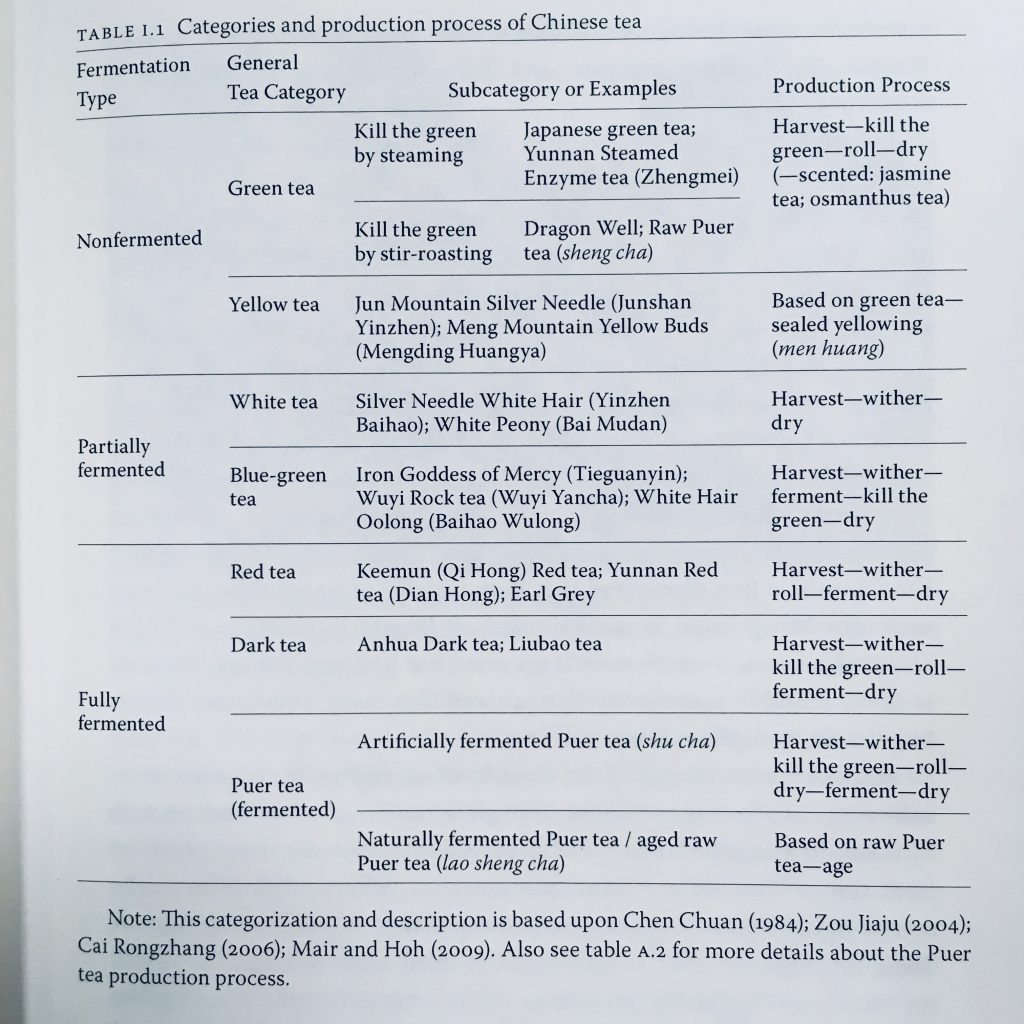

There is a lot of research on tea classification. Some tea masters identify five, but in the table below, Zhang (2014) identifies six different types of tea as they relate to fermentation: green, yellow, white, blue-green, red, and dark (also referred to as black), which are further split into sub categories.

In my travels, tea masters have recommended cold, filtered water as a base for their tea (clean and flavourless without additional residue from hot water tanks/pipes, as to not compete with any flavours from the tea); much like baristas recommend for their coffee. “The quality of water is particularly important in the Chinese Art of Tea. Even the best quality tea leaf cannot yield its precious treasures if the water to steep it is contaminated with chemicals and distorted with abnormal energies,” (Reid, 2012). Water temperature is essential; not all tea can handle high heat. A general rule of thumb I have been taught is the darker the tea leaf, the hotter the water; this serves me quite well as my favourite tea is pu erh and I know I can put my kettle on at full blast. If you are curious about how to brew the perfect cup of tea according to tea type, I recommend this amazing resource on YouTube.

Teaware is a fun item to source, as you can choose a number of different products to brew your tea in. Porcelain or glass teapots are easy to source and can be used with any type of tea. A traditional gaiwan (photo lower most left) uses a small handleless bowl, saucer and lid: loose tea is placed inside, water added to the brim, and the lid placed on top. To pour you simply offset the lid to keep the leaves in, and pour the hot liquid into the next vessel. WARNING: controlling the lid and body while pouring is a balancing act, don’t forget the contents are hot, so be careful as to not burn your fingers.

A traditional terracotta pot (photo lower most right) is a beautiful option to brew tea in. The porous nature of the material allows the tea to breathe, hold heat, and the tea will season the pot, which will make subsequent brews even better. These teapots need to be treated with additional reverence and can be somewhat likened to western culture’s appreciation for cast iron pans: only one type of tea per pot as to not mar the seasoning and do not wash the pot with soap and water. Maintain the pot by brewing its tea in it, and pouring its tea on it.

Tea in a porcelain gaiwan

Clockwise top left: A green porcelain teapot and cup, a screen filter on a stand, and a hand-painted porcelain fairshare mug

Tea is poured from a seasoned terracotta teapot through a screen filter and into a glass fairshare mug

In the middle and right photos above, there is a piece of teaware called a fairshare mug that is typically paired with a colander-like device that is a small bowl with a fine mesh screen (to ensure a minimum of leaves make it into your cup). When tea is brewed, the stronger tea will be closer to the leaves and the weaker tea will be further away. The use of the fairshare ensures that the tea brewed in the pot is evenly distributed by mixing the stronger and weaker portions of the pot together. An item that I haven’t shown are the bamboo tools that are used to move the tea from its container to the teapot; the goal is not to handle the tea with your hands so as not to contaminate the leaves.

In Part I of this series I mentioned a 2010 trip to Hong Kong and mainland China that forever changed how I consume Chinese tea. On the tail end of our adventure, we ventured from the Kowloon side to the Hong Kong side to my family’s favourite tea shop to stock up on our tea necessities (this was especially poignant after relying on their pu erh while in mainland China to get me over my temporary ailment). The shop’s tea master honoured us with sample pourings of two different teas; each brewed traditionally, in gong fu cha style, in a small terracotta teapot.

Jasmine tea rolled into individual balls

White tea brewed in a terracotta pot

Tea brewed in a terracotta pot is transferred to a glass fairshare mug before being served

The flavours and aromas coming from these tiny cups was astounding. Delicate, floral, and clean are the best words to describe what my palate was exploring. Never had I experienced tastes so profound. I was hooked. Since that trip, I’ve been trying to learn more and more about Chinese tea and serving it in the same relative manner that the Hong Kong tea master did. I was also extremely fortunate to be living in the lower mainland of BC when I returned to Canada and began frequenting the shop of a second-generation tea master. When it comes to Chinese tea, she is one of the most knowledgeable, personable, and passionate individuals I’ve encountered. She never hesitates to take the time to teach you about her craft.

As a reminder, we have a number of fantastic resources on Chinese Tea in our University of Alberta holdings. My go-to print items are below, as well as a link to my FAVOURITE database:

- Bloomsbury Food Library

- Lü, Y. (1974). The classic of tea (F. R. Carpenter, Trans.). Ecco Press. (Original work published 804)

- Reid, D. (2011). The art & alchemy of Chinese tea. Singing Dragon.

- Tong, L. (2012). Chinese tea. Cambridge University Press.

- Wang, L. (2005). Tea and Chinese culture. Long River Press.

Thank you for reading! The subject of Chinese tea is so broad and diverse, it is sometimes hard to narrow down information into a format best suited to this blog. If you would like a taste of a traditional pouring of Chinese tea, please check out this clip on YouTube -> it starts at 33:56. I hope that this blog series has inspired you to delve more into the topic and into our recently-reopened library stacks!

Like our blog posts? We invite you to subscribe to our newsletter (scroll down to the bottom right side of this page). Love us on the blog? Then you’ll love us on social media! Check us out at @uofalibrary on Instagram, & Twitter!