This post is written by Map Collection Staff, Larry Laliberte & Bonnie Gallinger.

The Indigenous Peoples and Canada’s National Parks guide is a multidisciplinary literature review that introduces the historical and current relationship of Indigenous people and Canada’s National Parks. The creation of this guide is part of ongoing work to re-positioning the William C. Wonders (WCW) map collection.

This guide is an example of the growing awareness that Indigenous peoples’ experience in the creation of Canada’s National Parks is a continuation of the process of settler colonialism. By highlighting omissions and absences embedded in these mapped “national interest areas” the guide’s resources contribute to an ongoing procession to deconstruct maps (and colonial collections) that are historically taken as-is, both in terms of their cartographic representation and the social good/environmental myths that encase them.

An important part in the creation of this guide is the concept of counter mapping. Counter-mapping can be summarized as the power relations in western maps being confronted through the use of methods like re-territorialization, co-authorship, critical GIS and counter mapping.[1] Counter-mapping provides a way for Indigenous communities to make use of various geographical/cartographical techniques to communicate their own territorial claims and counter competing claims of others.[2]

When digital copies of print maps are made available online they are often presented “as is” with little context beyond the metadata (detailed or threadbare) associated with the digital object. If there is related information, it tends to lean heavily on celebration, focusing on the science of surveying and government/environmental policies that established these spaces in the “national interest”.[3] “Protected spaces” are promoted by government, and conservation groups, as travel destinations where one can embrace the beauty of nature.[4]

These cartographically enclosed areas continue the ongoing erasure of Indigenous peoples and their relationship to the land. Often missing in the presentation of online historical map collections is research materials that “counter” the map. Conversations between map staff and the MLIS practicum student working on this guide, Olesya Komarnytska, illuminated the accumulation of knowledge that had been built as a result of various reference questions relating to Indigenous land dispossession with the creation of Wood Buffalo National Park.

These discussions led to the pulling together the various threads of research materials related to counter-mapping, park histories and Indigenous land dispossession, so that in addition to the map scans and their database attributes, a detailed subject guide focusing on Indigenous Peoples and National Parks in Canada could be created to provide deeper context to these maps beyond passive points, lines and Eurocentric place names to shine a light on the spaces they “occupy”.

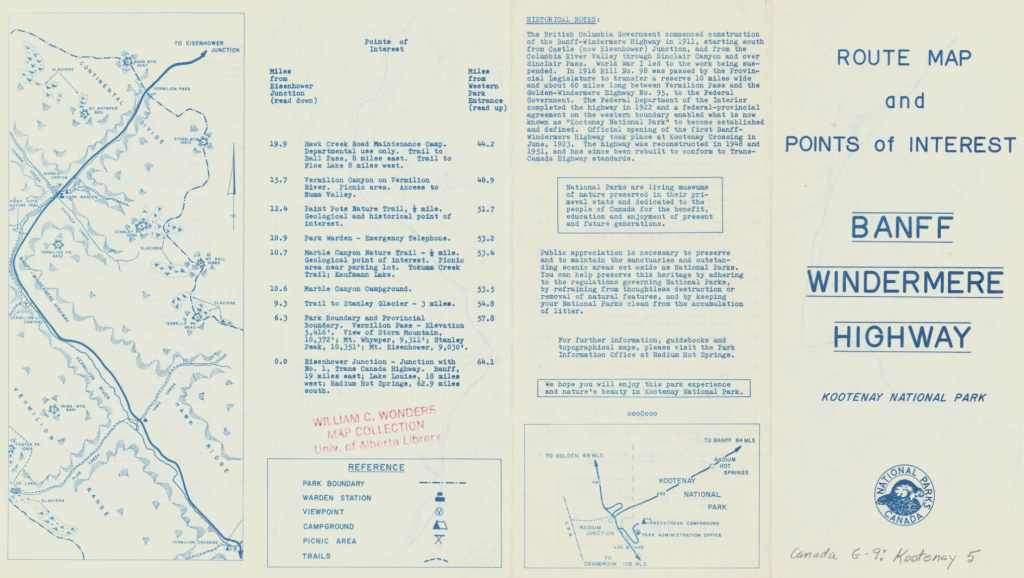

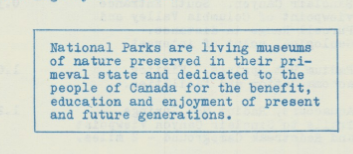

The fragments of this light can be found on the verso of many national park maps through the text and images used to highlight the features enclosed within park spaces. Within this attribution one can see the invoked “national interest”. For example, a 1965 route map of the Route Map and Points of Interest Banff Windermere Highway Kootney National Park states:

“National Parks are living museums of nature preserved in their primeval state and dedicated to the people of Canada for the benefit, education and enjoyment of present and future generations.”

National Parks Canada (n.d.) Route Map and Points of Interest Banff Windermere Highway Kootney National Park Retrieved from https://archive.org/download/NP171965/NP171965.jpg

With such declarations one must ask – for who’s benefit, and at whose expense? Yet, this textual and spatial representation of settler-colonial cartographies presents evidence that can lead to their reinterpretation, enabling researchers to unlock interlocking systems of power.[5]

In part 3 of this project’s story we will explore the collaboration and partnerships behind the scenes. If you missed the first part, you can read it here.

- Warner-Smith, A.L. (2020). Mapping the GIS Landscape: Introducing “Beyond (within, through) the Grid”. International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 24(4), 767–779.

- Willow, A.J. (2013). Doing Sovereignty in Native North America: Anishinaabe Counter-Mapping and the Struggle for Land-Based Self-Determination. Human Ecology 41, 871–884.

- Parks Canada and Canadian conservation groups both argue that national parks and wilderness areas are established to benefit all Canadians. To use a popular phrase, it is in the “national interest” to establish such parks. Native peoples in Canada are generally apprehensive about this argument. The Cree band land entitlement in Wood Buffalo National Park : history and issues. Circumpolar pamphlets https://archive.org/details/creebandlandenti00mcco/

- Library of Congress https://www.loc.gov/collections/national-parks-maps/about-this-collection/

- Fujikane, Candace. (2021). Mapping Abundance for a Planetary Future. Duke University Press.