By David Sulz, Public Service Librarian

You can access tens of thousands of Chinese-language items through University of Alberta Library, many of which are not on the open internet. We have physical and electronic items; historic and recent; scholarly and popular non-fiction; poetry and fiction; newspapers and magazines; music and film; art and photography; and even primary source documents.

We collect them for everyone from fluent Chinese speakers, to language learners, and even those with no language ability but who enjoy international film, music and art.

Finding them is the fun part (if you include “challenge” in your definition of “fun”).

First, where to look.

Many of our 1600 specialised search databases have some or many Chinese items. Here are a few:

- “Search the library” has a variety of books and articles and “publication types”, but only searches a small portion of our resources.

- Enter a search term in English or Chinese (or other languages) then choose the language filter on the results page.

- To browse more randomly, click on advanced search then choose Chinese under language (without entering any search terms).

- Use facets on the left to select a specific location (e.g. Rutherford or Bruce Peel Special collections), or a discipline-specific database, a certain publication type, or others.

- Audio and video subject guide

- See the “streaming…” tab (e.g. Kanopy, Criterion on Demand, Smithsonian Global Sound) or the “physical …” tab (for DVDs and CDs)

- Some interesting/unusual collections (more here: East Asian Studies)

- China Academic Journals (CAJ, CNKI) (academic sources)

- Airiti Library: Taiwan Electronic Periodicals Service

- Scripta Sinica: Classical Chinese Studies

- Chinese Cultural Revolution Database

- Siku Quanshu (the largest single assembly of Chinese classical works)

- PressReader (recent newspapers and magazines, select “catalog” then languages menu)

- Shen Bao (newspaper)

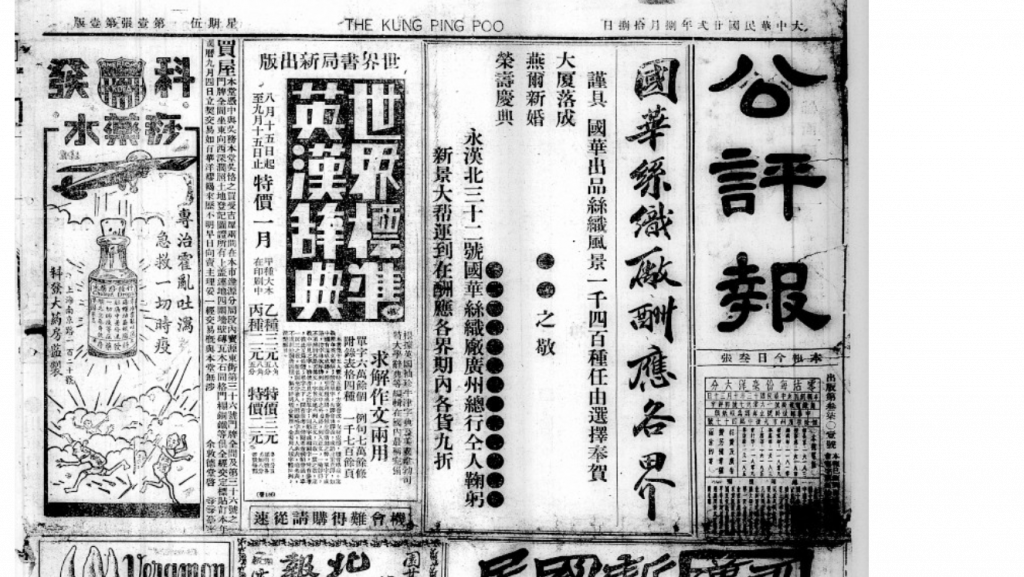

- Late Qing and Republican-Era Chinese Newspapers

Next, how to search

Here are a few general principles to keep in mind.

- Search engines search the information in an item record and Chinese sources might be recorded in Chinese characters or with roman (English) letter transcriptions, or both.

- Chinese characters might be in traditional style or simplified style

- Transcriptions might be in pinyin or Wade-Giles

- Chinese doesn’t have spaces between words but catalogue records might

- There are several ways to enter Chinese characters into search engines

- Easiest: cut-and-paste characters from a website, email, or digital copy of a paper (I often get them from English wikipedia articles on Chinese topics).

- Keyboard entry: change the language and keyboard settings on your computer (search the internet for how-to instructions).

- Some computers allow handwriting entry (trackpad, mouse, stylus)

As an example (and here comes the “fun” part), say you were looking for the Dao De Ching (popular text on the philosophy of Daoism) in our “search the library” box. Just the simplified Chinese characters 道德经 gives 1479 results.

- Conveniently, English wikipedia gives many character/transcription variations.

- The traditional characters 道德經 give 59716 results but using quotation marks to specify all three characters must appear in that order (i.e. “道德經”) focuses in on 1611 results.

- The pinyin transcription “Dàodé Jīng” (without using the tone marks for searching) gives 858 results but “dao de jing” gives another 1852 results while “daodejing” gives 1210 more.

- The Wade-Giles transcription, “Tao Te Ching” gives 3665 results while “taoteching” gives another 52.

A fairly complete search incorporating all of these might look like:

“道德经” OR “道德經” OR “daode jing” OR “dao de jing” OR “daodejing” OR “tao te ching” OR “taoteching”

This gives 5984 results in our “search the library” box, which, you’ll remember, is just one place to search. By the way, not all search engines let you use boolean AND/OR (nor other techniques like truncation or proximity), so you might have to do a bunch of single searches.

Now that we’ve accounted for probably all the possible combinations, we could narrow by language to Chinese. Interestingly, there are 3 choices for Chinese language in these results pulled from many different search engines: Chinese (490), 繁體中文 (287), and 簡體中文 (173).

Alternatively, we might try the subject term “taoism” which is common to many of the titles we found above to find other works on the topic – but that’s a whole other approach (ask me sometime if you dare).

This is probably more than enough for a “brief” overview of finding Chinese language items through our library. Obviously, it can be pretty complex depending on how thorough you want to be.

The key message is: don’t be shy about asking questions. No one in the library is an “expert” per se (this isn’t a Chinese library after all) but we do enjoy exploring along with you and sharing our expertise in figuring out how different tools work.

One last thought. We have thousands of items in other languages, including Japanese and Korean, for which many of the ideas above can be adapted.

Happy searching,

David Sulz, academic librarian.

If you need help looking for resources, whether they be in English, Chinese or another language, please reach out and Ask Us!