By Kelsey Kropiniski

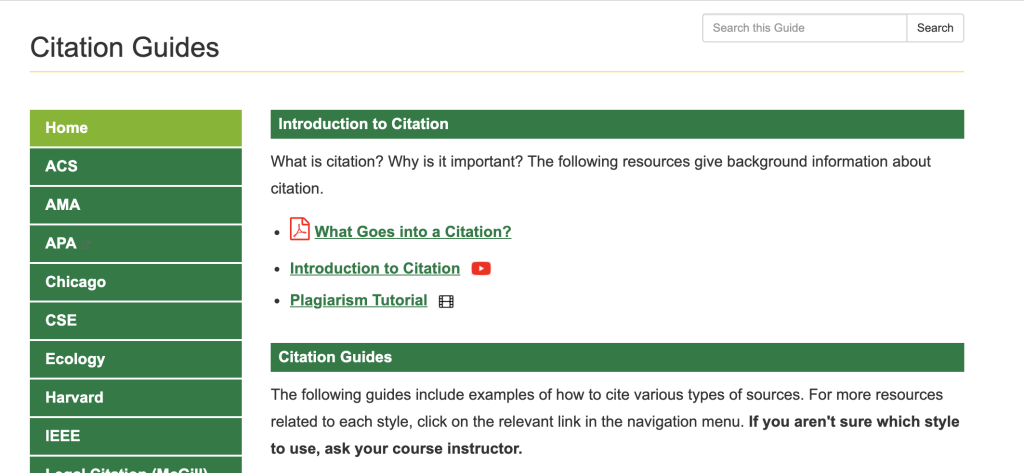

One of the most common ways that we support students in their writing here at UAlberta Library is by offering citation advice. Citation questions come up frequently, and usually when they occur we direct students to the citation guides on our website. From there, we try to find the correct style and format to help students properly cite the source material they’re working with. Sometimes citation isn’t simple. As with most things that have strict rules and regulations, citation styles like APA, MLA, and Chicago can be highly exclusionary to different forms of information – especially when it comes to Indigenous oral teachings.

For decades, Indigenous scholars have called for better ways of acknowledging Indigenous voices in academia. Many of our structures within the academic world today are rooted in Eurocentric systems that have always placed a higher value on Western knowledge rather than Indigenous oral traditions and ways of knowing. Citation is undoubtedly one of these structures.

Citation styles and formats allow us the chance to formally acknowledge the information that we have learned from others; however, these styles disproportionately prioritize information that’s been written down. Because so much Indigenous knowledge is held within oral traditions and ways of knowing, citation acts as a barrier to the respectful inclusion of Indigenous voices in academia. In their article “More Than Personal Communication: Templates for Citing Indigenous Elders and Knowledge Keepers”, Lorisia MacLeod states that oftentimes when attempting to integrate oral teachings into academic writing, Indigenous scholars are encouraged to cite the oral information as a ‘personal communication’. They argue that “to use the template for personal communication is to place an Indigenous oral teaching on the same footing as a quick phone call, giving it only a short in-text citation (as is the standard with personal communication citations) while even tweets are given a reference citation” (2021, p. 2).

In partnership with the staff at the NorQuest Indigenous Student Centre, Lorisia MacLeod developed the following templates as a way to cite Indigenous knowledge. Rather than citing a personal communication, using these templates is one small way that we can represent Indigenous knowledge as being of equal value to the books and articles we read.

The Templates

The following templates are taken directly from Lorisia MacLeod’s article, and can also be found here on our library website on our Indigenous Research Guide.

APA

Last name, First initial. Nation/Community. Treaty Territory if applicable. Where they live if applicable. Topic/subject of communication if applicable. personal communication. Month Date, Year.*

For example:

Cardinal, D. Goodfish Lake Cree Nation. Treaty 6. Lives in Edmonton. Oral teaching. personal communication. April 4, 2004.

MLA

Last name, First name. Nation/Community. Treaty Territory if applicable. City/Community they live in if applicable. Topic/subject of communication if applicable. Date Month Year.*

For example:

Cardinal, Delores. Goodfish Lake Cree Nation. Treaty 6. Lives in Edmonton. Oral teaching. 4 April 2004.

* Use hanging indent paragraph style: after the first line of each citation, indent 0.5″ from the left margin.

Need help with a tricky citation? Ask Us!

Love our blog posts? You’ll also love us on social media! Check us out at @uofalibrary on Instagram, & Twitter!

References

MacLeod, L. (2021). More Than Personal Communication: Templates for Citing Indigenous Elders and Knowledge Keepers. KULA, 5,1-5. https://doi-org.login.exproxy.library.ualberta.ca/10.18357/kula.135